Yield curve inversion and negative bond yields – is it different this time?

With cash and term deposit returns at all-time lows, a puzzling absence of inflation across the globe, gold prices reaching new highs in dozens of currencies (including AUD), and increasing equity market volatility, risk-sensitive investors are buying government bonds so enthusiastically that yields are falling below zero in some cases. In fact, with long-term bond yields falling faster than those at the short-end, yield curves have begun to invert. While historically this event has been a portent to economic weakness, the interpretation of this inversion could be more difficult this time round because the overall starting point for yields is so much lower than the past. Developments in the currency and commodity markets suggest that global capital is seeking to maintain liquidity, safety, and if possible secure positive carry. For investors in corporate bonds, many parts of the credit market still offer positive yields. However, a prolonged period of low or negative sovereign yields is a unique situation that could have unintended negative consequences, although we see little evidence of this to date.

Patience – and the art of spotting traps

Following two 25bp rate cuts by the RBA in June and July, banks wasted little time in passing these through to savers (and borrowers to a lesser extent). As a result, conservative and yield-dependent investors are being pressured to consider taking on additional risk by contemplating alternative asset classes or reweighting portfolios toward riskier assets.

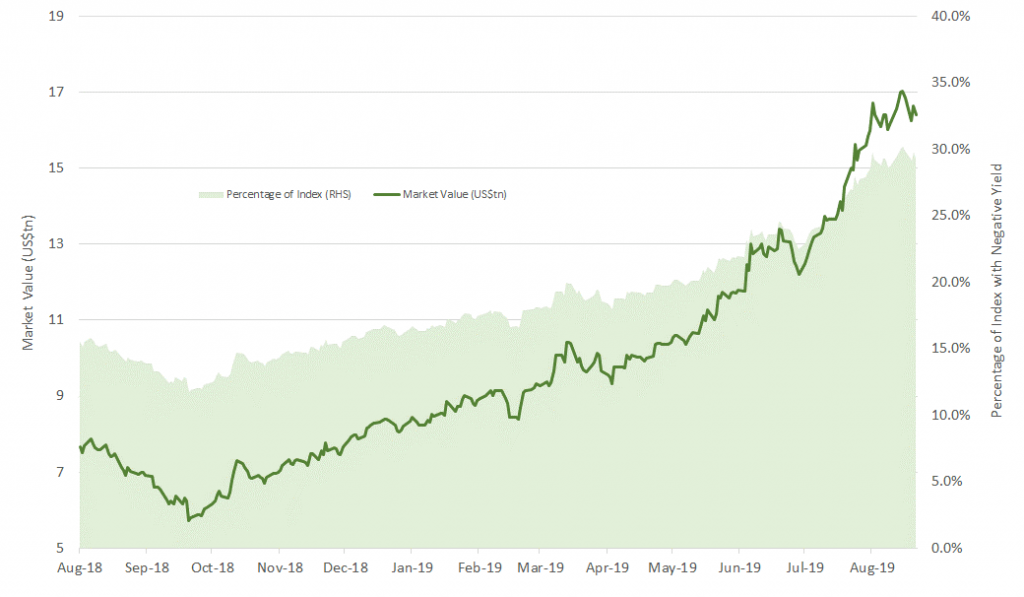

A prominent economic theory known as the “Keynesian Liquidity Trap” states that as interest rates fall, preference for physical cash increases over holding a liability that yields such a low rate of interest. Central bank QE policies essentially seek to trigger this process, as it is assumed that growing cash holdings would eventually induce consumption, and/or new capital investment, stimulating economic activity in the process. However, as the market value of bonds with a negative yield continues to rise, it is clear investors are willing to be patient, seeing these bonds as financial equivalents of a “mattress” under which they would otherwise store physical cash. In economic terms, (negative) time preference is winning the day, ahead of liquidity preference.

Figure 1: Market Value of Negative Yielding Debt

Source: Bloomberg

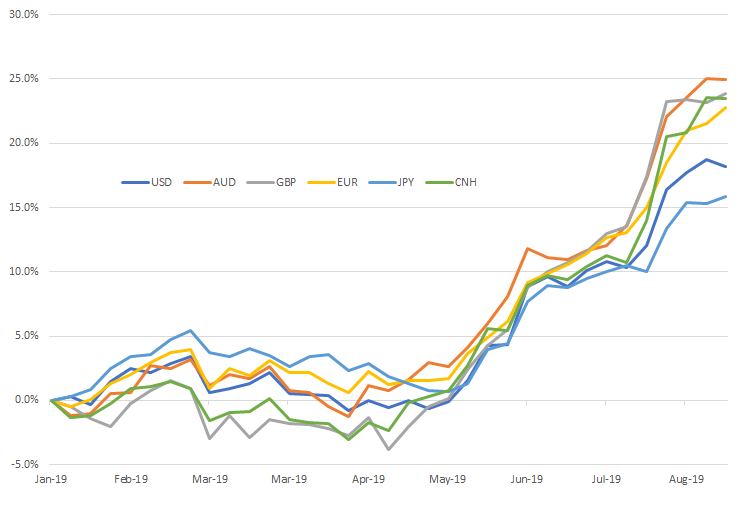

Other factors are suggesting that the global trend of falling yields is not an anomaly. The value of gold has been reaching new highs in a range of currencies, including Australian dollars and British pounds. If a government bond yield is very low or negative, there is no functional difference between owning the bond and buying gold, which preserves current purchasing power, is relatively liquid, does not produce a yield and incurs storage and insurance costs.

No government or central bank has been able to generate any meaningful inflation during this cycle. Another interpretation of strong precious metal prices is investors shifting currency savings into an asset that would protect the real purchasing power of those savings should central banks make another attempt to stimulate via quantitative easing. With the improbable but devastating prospect of disinflation or deflation in major markets, we believe that new QE programs would be larger and more aggressive than those previously. Hence, gold prices are showing broad global strength as investors re-assess their relationship with the “barbarous relic”.

Figure 2: Performance of Gold, Selected Currencies

Source: Bloomberg

Inverted yield curves – will history repeat, rhyme, or is it different this time?

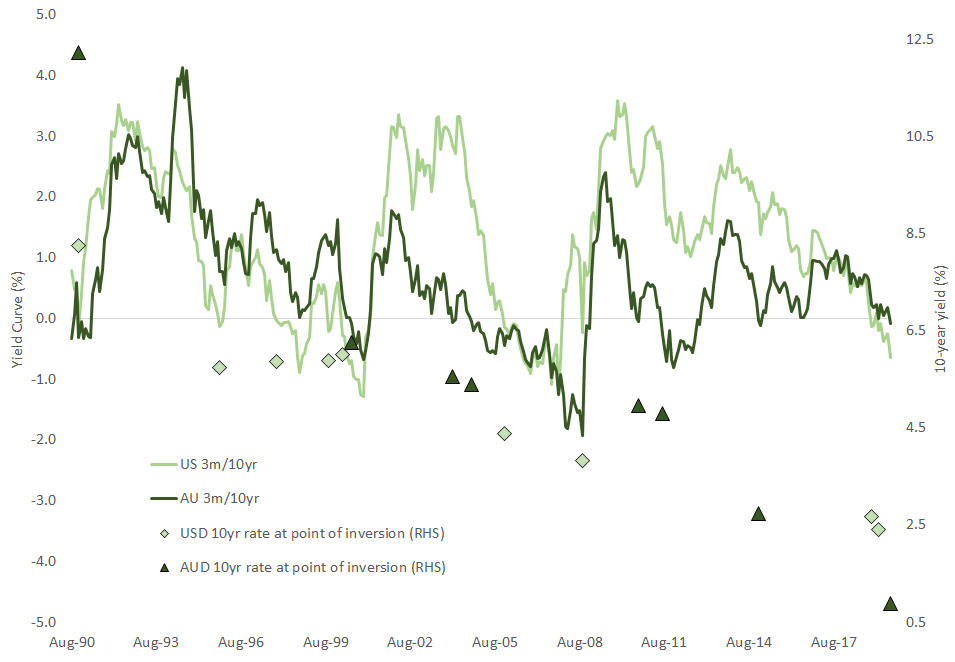

Yield curves typically have a positive slope, indicating that investors require a higher yield to lend money for longer periods. Some investors use longer bond yields as a proxy estimate of the future inflation rate. Most investors agree that the slope of the curve is an important indicator, but interpreting its meaning is always open to debate. A “typical” yield curve inversion is caused when a central bank raises short-term rates to contain inflation or cool an overheating economy, in the process sowing the seeds of a slowdown or recession. Up until the end of 2018, only the US Federal Reserve had been able to consistently increase rates against a backdrop of strong employment data. However, in 2019 the mood has shifted so dramatically that not only are central banks now cutting rates, but long-term rates are falling even quicker.

The expectation of renewed quantitative easing (QE) has played a key role. A constant companion of global investors since 2009, more recently a mixture of concern over trade tensions and future inflation expectations have influenced yield curves. In fact, it is possible that QE has been so influential in effecting the yield curve that the signals coming from it are not the same as prior episodes of inversion. Furthermore, inversions have never occurred with rates this low, creating additional uncertainty around the side effects of sustained low interest rate policy.

Figure 3: Long-Term Rates and the Yield Curve

Source: Bloomberg

Low interest rates and credit – can they learn to get along?

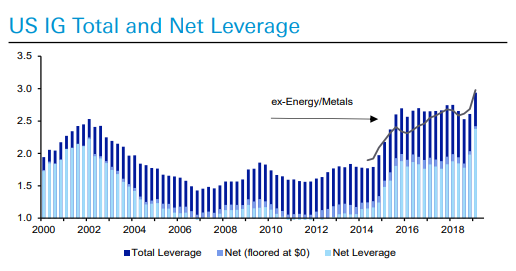

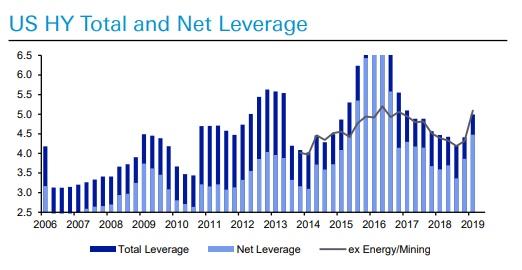

Low interest rates have generally been good for credit markets, allowing maturities to be refinanced at better rates and borrowers to service existing debt more easily. Corporate treasurers have obliged, increasing leverage to record highs. In a rebuke to central bank wishes, investment grade borrowers have favoured share buybacks rather than new investment, depriving economies of much needed activity. High yield borrowers have shown greater discipline, including several high-risk sectors such as the retail sector, and the oil and gas sector which is struggling with weak commodity prices.

Figure 4: US Credit Market Leverage

Source: Deutsche Bank

Lower financing costs are a double-edged sword, in that they should be creating more investment opportunities with positive present value, but flat yield curves make the returns on these projects lower and/or require longer investment horizons. Eventually, existing projects will reach the end of their useful lives, but firms will still need to service the debt issued to buy back shares in prior years. Low interest rates will keep this debt affordable for the foreseeable future, but ongoing refinancing requirements mean issuers will be reliant on markets when it comes time to roll these obligations.

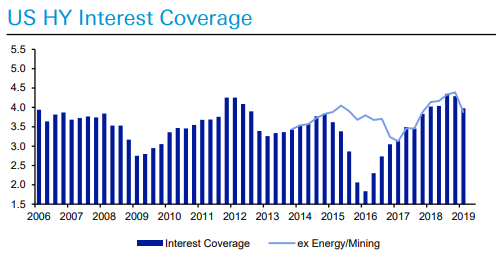

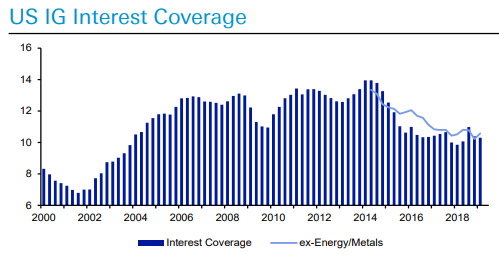

Figure 5: US Credit Market Interest Coverage

Source: Deutsche Bank

Leverage measures could continue setting or re-testing highs the longer rates remain low. In this scenario, a strong economy is increasingly necessary to support debt serviceability. Credit markets are still sanguine on corporate fundamentals, despite some spread volatility in August, but will become increasingly sensitive to the outlook if leverage continues to creep higher.

Conclusion

The increasing prevalence of negative interest rates, inverted yield curves and other such pricing anachronisms is unprecedented in modern times. Central banks have played a pivotal role in causing these anomalies, and bond market pricing suggests that investors believe that, in the absence of inflation, they have little choice but to continue following these trends. The prevalence of negative yields and the performance of “currency independent” assets such as gold reinforces this view. Inverted yield curves are watched closely as recession predictors, but may not be as reliable at this juncture because of the influence of non-market factors on yields. Credit markets, especially high yield, have largely resisted the temptation to re-lever, but recent data suggests this may be changing. Overall, despite what we expect to be an extended period of unconventional bond market activity, we believe credit market fundamentals are still sound and retain a constructive view for the next 6-12 months.

Disclaimer: Please note that these are the views of the writer and not necessarily the views of Daintree Capital. This article does not take into account your investment objectives, particular needs or financial situation.