How can we best achieve ESG and sustainability outcomes in fixed income? In our view, there are two primary avenues– directly, by investing in green, sustainable, or sustainability-linked (GSS) instruments, or indirectly by supporting those companies with the most credible plans and/or strongest progress on stated goals. This article will, in part, examine some of the strengths and drawbacks of each option. Engagement can add further credibility to your strategy if it is tailored to the chosen investment approach. Professional investors address an ever-present tension between investing based on a set of sustainable or ethical values, and the fundamental fiduciary duty to prioritise returns. Recent months have reinforced our view that reconciling these outcomes involves subjective compromise based on the prevailing investment climate, regulatory settings, and expected holding period.

“Green” bonds – targeted and defined

The term “green bonds” is often used as a catch-all term to describe the vast range of instruments available in this sub-sector of the fixed income market, but for this article we may also use the acronym GSS as defined above.

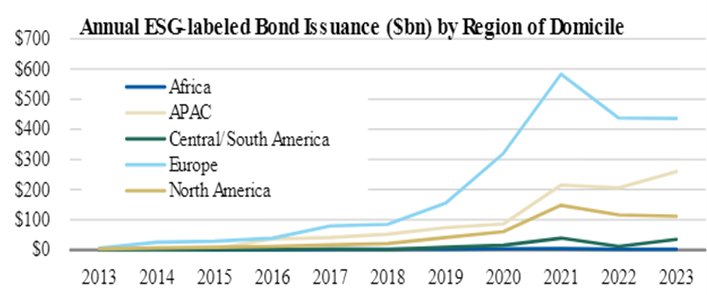

The GSS market in total issued a record $US845bn in 2023, representing about 6.3% of gross issuance. This compares to GSS issuance representing 5.6% and 6.1% for 2021 and 2022 respectively. As Figure 1 shows, European issuers have been leading the way since 2016, but in 2023 it was APAC issuers that were the drivers of growth.

Figure 1

Source: Morgan Stanley

Excluding 2021, which was a blockbuster year for issuance across the board, the GSS market continues to expand. Growth rates have been moderating in the corporate bond environment, driven by reluctance of some issuers to pigeonhole capital into such specific uses, and investor concerns around the structure of some types of green bonds. One such structure is the Sustainability-Linked Bond (SLB), which we will discuss in further detail shortly.

One distinct advantage of green bonds is their specificity of structure, target and/or outcome. Impact investors can have confidence that capital invested in these offerings is supporting tangible action toward sustainability outcomes, while also being able to quantify this progress based on regular progress reporting.

Some of the structures available include:

- use of proceeds (largely environmental, social or sustainability);

- thematic use of proceeds (such as blue bonds designed to support water-related projects);

- taxonomy-aligned bonds (use of proceeds linked to taxonomies such as the UN Sustainable Development Goals);

- Sustainability-Linked (bonds with specific embedded targets or outcomes, where failure incurs financial penalties for the issuer); and

- transition bonds (related to the energy transition).

The most topical of these structures is the SLB. In short, investors and issuers enshrine specific outcomes into bond documentation, with penalty interest payable if these outcomes are not achieved.

In our view, the incentives in this type of structure are mis-aligned. Fundamentally, achieving sustainability targets requires capital (from bond proceeds, for example) and time (project planning and execution), diverting human capital from other tasks. If the penalty interest charge (usually in the form of a step-up in the bond interest rate) is set too low, the issuer may see it as part of the overall cost relative to the diversion of other resources required to achieve the target. If set too high, they may choose to raise traditional debt capital with fewer restrictions or abandon the bond offering altogether.

Green bonds do have downsides. It is an unfortunate fact that environmental and sustainability projects are very often greenfield, rely on new or emerging technology, have underdeveloped value chains, or embryonic end-user markets.

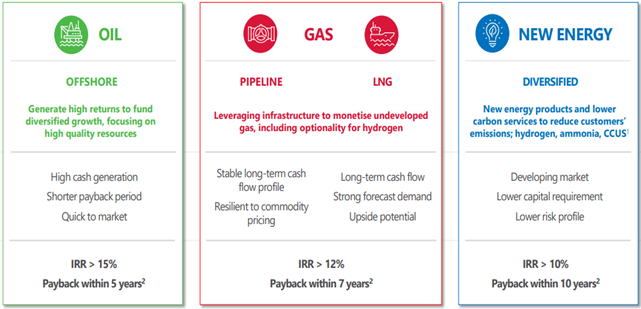

The nascent market for sustainably produced hydrogen is an excellent case-in-point. While the prospect of a renewable fuel that produces only water as a “waste” product is enticing, the implementation of a global scale industry has been slow to materialise. Woodside Energy is a good example. Being in the global energy production and transport business should be an ideal platform to develop these structures. However, even before any project specifics can be discussed, Woodside notes that new energy projects have longer payback periods in part because they are still in relatively early stages of development.

Figure 2

Source: Woodside Energy

The company has committed to spend $5bn by 2030 with an ambition to abate up to 5mtpa of CO2e, but the CEO has admitted that this goal may not be reached as customers baulk at the higher costs of green energy products compared to the existing “grey” equivalents. Unfortunately, no amount of green financing or green leadership can balance the iron law of supply and demand.

The structuring and sale of green bonds does allow for a targeted form of engagement. By seeking involvement in the consultation phase of a new issue, investors can express their preferences, concerns, and test the assumptions underlying an issuer’s sustainability strategy. Issuers who take this process seriously are more likely to attract capital at attractive pricing.

Green Leaders – supporting the vanguard

Investing through a sustainable lens can also involve identifying companies that are leading by example. By directing investment dollars toward these green leaders, we can indirectly achieve sustainability goals.

There is no precise definition of a green leader, but prerequisites include:

- Cultural buy-in from all levels of the business;

- A comprehensive and coherent strategy to reduce emissions or achieve stated targets; and

- Strong underlying business fundamentals.

To demonstrate the concept of green leaders, consider Figure 3. The white line is the total return of a long-running sustainability ETF (Invesco WilderHill Clean Energy ETF, NYSE: PBW). The purple line is one of its constituents, Italian “poles-and-wires” giant Prysmian Group, which in FY23 reported EBITDA of EUR1.6bn, Return on Capital Employed (ROCE) of 23% and a dividend payout ratio of 36%.

The ETF has had moments of strength, but overall has been disappointing. In our view, the thematic focus of PBW meant that reliable performers such as Prysmian were combined with much smaller and younger businesses akin to venture capital investments. When all those venture capital businesses are essentially exposed to a single sector, risk is magnified and the contribution of companies like Prysmian are diluted.

Figure 3

Source: Bloomberg

We believe that a bias toward green leaders can be effective in maintaining returns, managing risk, and progressing sustainability.

Profitable companies have the resources to implement climate and sustainability plans. Using a mixture of retained earnings and debt financing, each project can have its profitability weighed against its specific cost of capital. Importantly, the cost and impact of any ESG or sustainability outcomes can be integrated into the analysis. Financing options may or may not include a GSS instrument but should not matter if the desired outcomes can be achieved.

A proper framework can also consider risks, including environmental and sustainability risks, at the project level. This is far more practical for managers who know their businesses best. But it is here where cultural alignment is important across the organisation. The board will not review every new project, and the CEO often delegates decision-making to senior executives, all of whom must be committed to the same goals. In our experience, dedicated departments tasked with implementing a sustainability agenda can become silos that compete for capital within the organisation, leading to sub-optimal outcomes for stakeholders.

Employees are the lifeblood of any business. Using a range of metrics for companies within the S&P 500, people rated their experience at their employers, which was then cross-referenced with the price-to-earnings multiples of those companies (Figure 4). The results showed that investors tended to pay materially higher multiples for companies where Senior Management and Culture and Values were rated well above median.

Figure 4

Source: Bank of America, Glassdoor, Factset

These results reinforce our point about cultural alignment and show that many of the ideals of ESG and sustainability are simply good business practice.

Fixed income investors have a contractual relationship with the issuer of a bond, and thus generally get less access to management and have comparatively less influence on company direction relative to equity owners. That said, mutually beneficial engagement is still possible. In our view, effective engagement with green leaders involves seeking to improve understanding of a business to identify best practices – both to implement internally and to share with other portfolio companies.

Conclusion

Sustainable investment continues to grow and develop. As the GSS framework evolves, fixed income investors can direct capital toward specific thematics or projects. Changing market conditions have seen investors and issuers become more discerning about the volume and type of GSS issued as part of the capital allocation framework. However, we have seen that green bonds are not the only way to progress environmental, social and sustainability outcomes. Profitable companies that are willing to develop a holistic strategy in which all employees are invested have been shown to achieve success, and the market has rewarded them accordingly in the form of higher valuations. Combining the best opportunities from both approaches will give professional investors the best chance to strike the right balance between ethical and fiduciary responsibility.

Disclaimer: Please note that these are the views of the author Brad Dunn, Senior Credit Analyst and Portfolio Manager at Daintree, and are not necessarily the views of Daintree. Some small changes were made to this article, based on updated information. This article does not take into account your investment objectives, particular needs or financial situation and has been prepared for general information purposes only and must not be construed as investment advice or as an investment recommendation.