Is my fund manager doing a good job?

Fund managers play an important role in the provision of secure retirements for millions of Australians. So it is important to be able to assess whether a fund manager is doing a good job on behalf of investors. It remains very common for market benchmarks to be used in this assessment process; for example, Australian equity managers may be assessed with reference to the S&P/ASX 200 Accumulation Index – the more they outperform, the better they are perceived to be.

When it comes to the fixed income asset class, however, this approach is problematic. In this piece, we will first outline the reasons why this is the case. We will then comment on alternative approaches and suggest a practical way to address the question of whether your fixed income fund manager has done a good job, or not.

Is indexing an appropriate framework?

Funds management is a very quantitative endeavor. The performance of managers is measured on a daily basis. The phrase “lies, damned lies, and statistics” comes to mind though, because our industry has many ways of defining success. The main one is outperforming a given market benchmark. In fixed income, the Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Index is one such benchmark. It contains a wide variety of bonds including those issued by governments, sovereign agencies and municipalities, and corporates. Each bond is weighted by its size; which means that the largest bond issuers are those with the largest index representation.

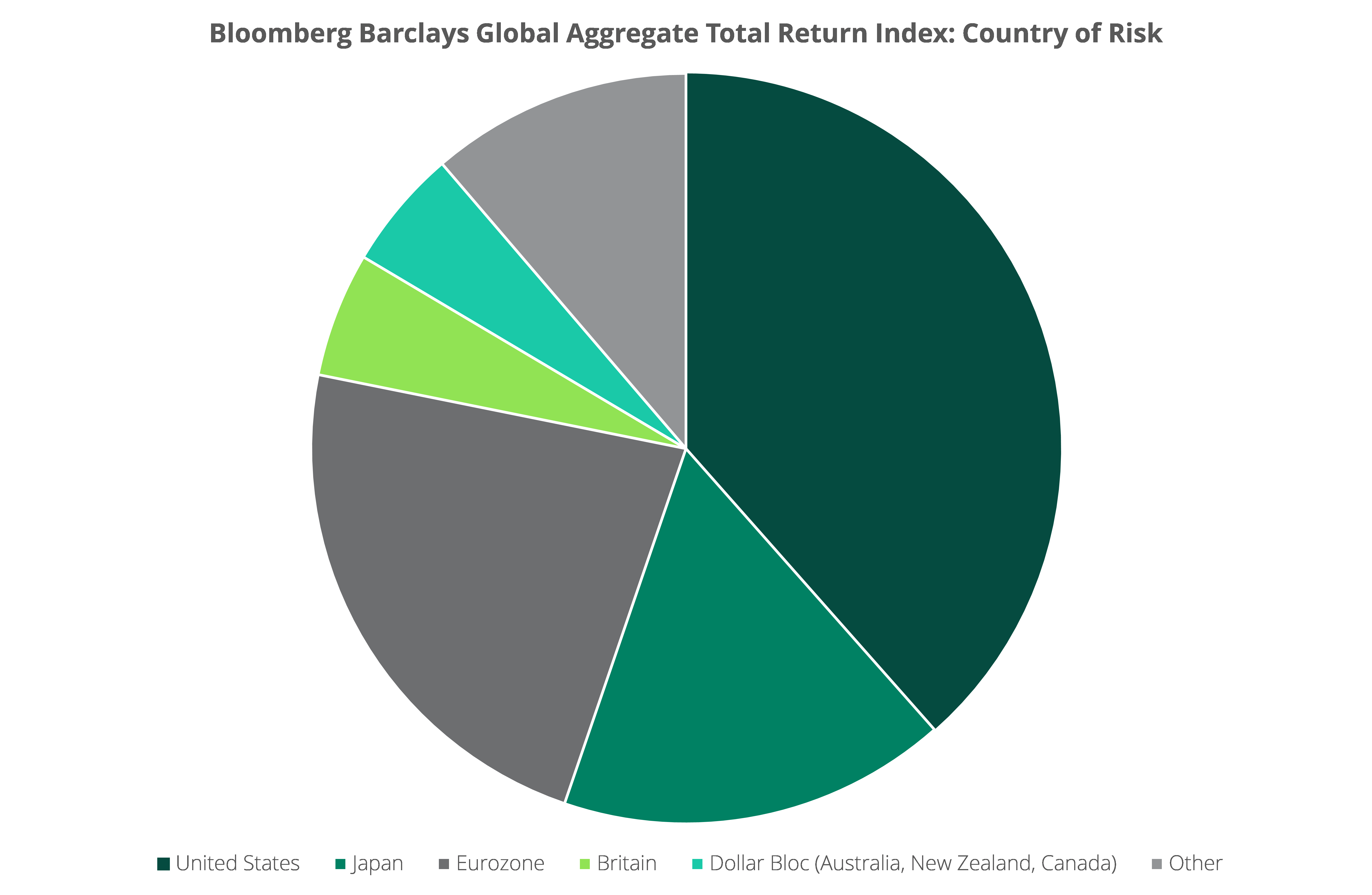

The Figure 1 below shows the country of risk grouping in the Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Index. Notice the predominance of the United States and Japan, which are two of the largest issuers of sovereign bonds.

Figure 1: Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Total Return Index: Country of Risk

Source: Bloomberg, Daintree (as at 24/09/2018)

Issue: Outsized investments in the largest issuers of debt

This is an important flaw of benchmarks in the fixed income universe. Remember, an entity issuing a bond is, all else being equal, increasing its debt. The more bonds that a company or other bond issuer has outstanding, the greater the representation that issuer will have in the index. Thus the United States and Japan are the largest countries represented in the Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Index. We could show other indices as well and the same issue would be apparent.

Investors who follow fixed income benchmarks are often compelled to invest ever greater amounts of money in the bonds of issuers with large amounts of debt already outstanding, eschewing more attractive risk-adjusted expected returns elsewhere. This clearly fails the common-sense test. In fact, the optimal approach to fixed income investing leads to the exact opposite situation, whereby investors allocate more cautiously to entities with more debt outstanding. Why? There are two main reasons that are best illustrated by comparing bonds to equities:

- An equity manager may be rewarded for a concentrated position in few stocks. A bond manager will not. In fixed income, upside returns beyond the income expected at the initiation of the investment are limited.

- Both equity and bond investors face the total loss of capital in the event that something goes wrong.

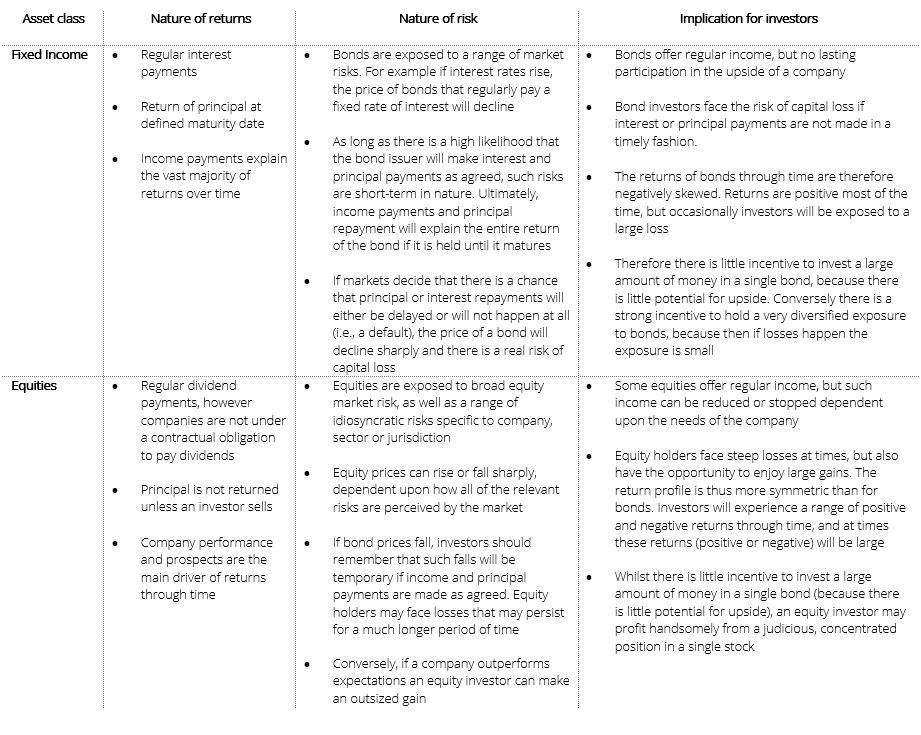

The table at the end of this paper contrasts the characteristics of bonds with those of equities more fully. For now, the main takeaway is that given the asymmetric risk profile of bonds it makes no sense to make large, concentrated bond investments. There is simply no likelihood of this sort of substantial upside performance that might justify an investor taking this sort of risk, and this is particularly the case where credit risk is heightened because an issuer already has a lot of debt outstanding.

Issue: Opportunity costs

Fixed income markets are extremely large and diverse, and are multiples of the size of equity capital markets globally. There is a huge diversity of issuers in the bond market for investors who are sufficiently resourced and incentivised to look for good risk-adjusted returns. This illustrates another problem with indices in bond markets: indices have become less representative of the rich opportunity set available, because increasingly they have become dominated by the issuance of large bond issuers, like governments. There is no single index that does even a reasonable job of representing the very large investable universe. That is the case locally, and even more so the case offshore. Thus, investors who use benchmark-focused approaches are suffering a meaningful opportunity cost. The index dictates investment decisions that should, in fact, be dictated by careful research of whether risks are being adequately compensated.

Issue: Timing of investment

In fact, investors who follow indices often incur actual costs too. Consider the decision a borrower faces when fulfilling their funding needs. Sometimes there is an imminent need that determines timing, but often the decision is based on price. That is, bonds will typically be issued when an issuer considers the cost of doing so to be low. Lower cost issuance means lower expected returns for investors and when investors bid up the price of some new issues because of likely inclusion in an index, expected returns are reduced still further.

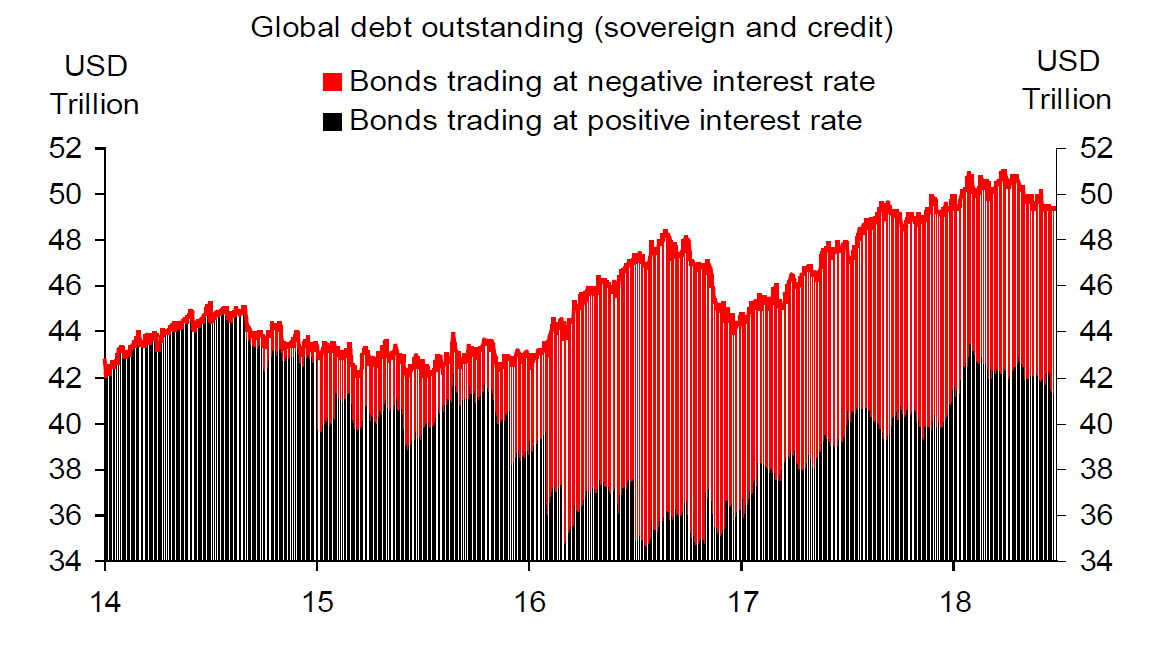

Once a bond enters a benchmark index, this cycle of perverse behaviour can continue. Consider what an investor should do if a bond increases in price by more than similar bonds. Given our comments earlier about the significant breadth of opportunity in global fixed income markets and also the limits to upside potential in fixed income investing, common sense might dictate reducing exposure. An appropriately directed research effort is likely to uncover another bond with a similar risk profile that offers investors a better income stream. Is this the course of action a benchmark-hugging investor is likely to take? Perhaps not. In fact, such an investor may feel compelled to do the opposite, because weightings in benchmarks increase with price. An egregious example is the massive issuance of bonds by government issuers engaged in quantitative easing. This has pushed the yields of an increasing basket of bonds into negative territory, as shown in Figure 2 below. Outside of official demand, much of the demand for these bonds is likely to come from investment managers who are beholden to market benchmarks. This is a point that bears highlighting: investors who follow market benchmarks are in some cases not even being paid an interest income by some bonds in their portfolio. Instead they are paying bond issuers for the ‘privilege’ of holding their stock so that they can replicate their chosen benchmark as closely as possible.

Figure 2: Stock of bonds with negative yields

Source: Deutsche Bank (as at 24/09/2018)

Issue: Flawed manager incentives

The issue of flawed manager incentives among those who follow a traditional approach to the management of fixed income portfolios extends still further. At a more basic level, this misalignment of incentives is at the heart of the rise of absolute return investment approaches. What services should a fixed income fund manager be providing for their clients? A benchmark-focused manager aims to outperform the benchmark; is this sufficient? If an index is down 2% and a fund manager is only down 1% the fund manager will be pleased with their efforts, but will the end investor also be pleased? Investors have many different risk/return preferences, time horizons and so on; but many view losing money as a poor outcome, full stop. They will not be satisfied if a fund manager outperforms a benchmark and yet still loses money. At Daintree, we believe that the strong growth of absolute return fixed income funds over time shows that this mismatch between fund manager incentives and investor expectations remains an issue among the end users of fixed income.

Issue: Interest rate risk

The final issue that we highlight concerns interest rate risk. Many fixed income indices are biased towards (and often exclusively focused on) fixed rate bonds. For example, the Bloomberg/Barclays Global Aggregate Index mentioned earlier has seen its duration drift from 5.3 pre-crisis, to more than 6 today. This is partly due to issuance patterns through time, but it is also reflective of the market environment because all else being equal, as interest rates fall the duration of fixed rate bonds increases further.

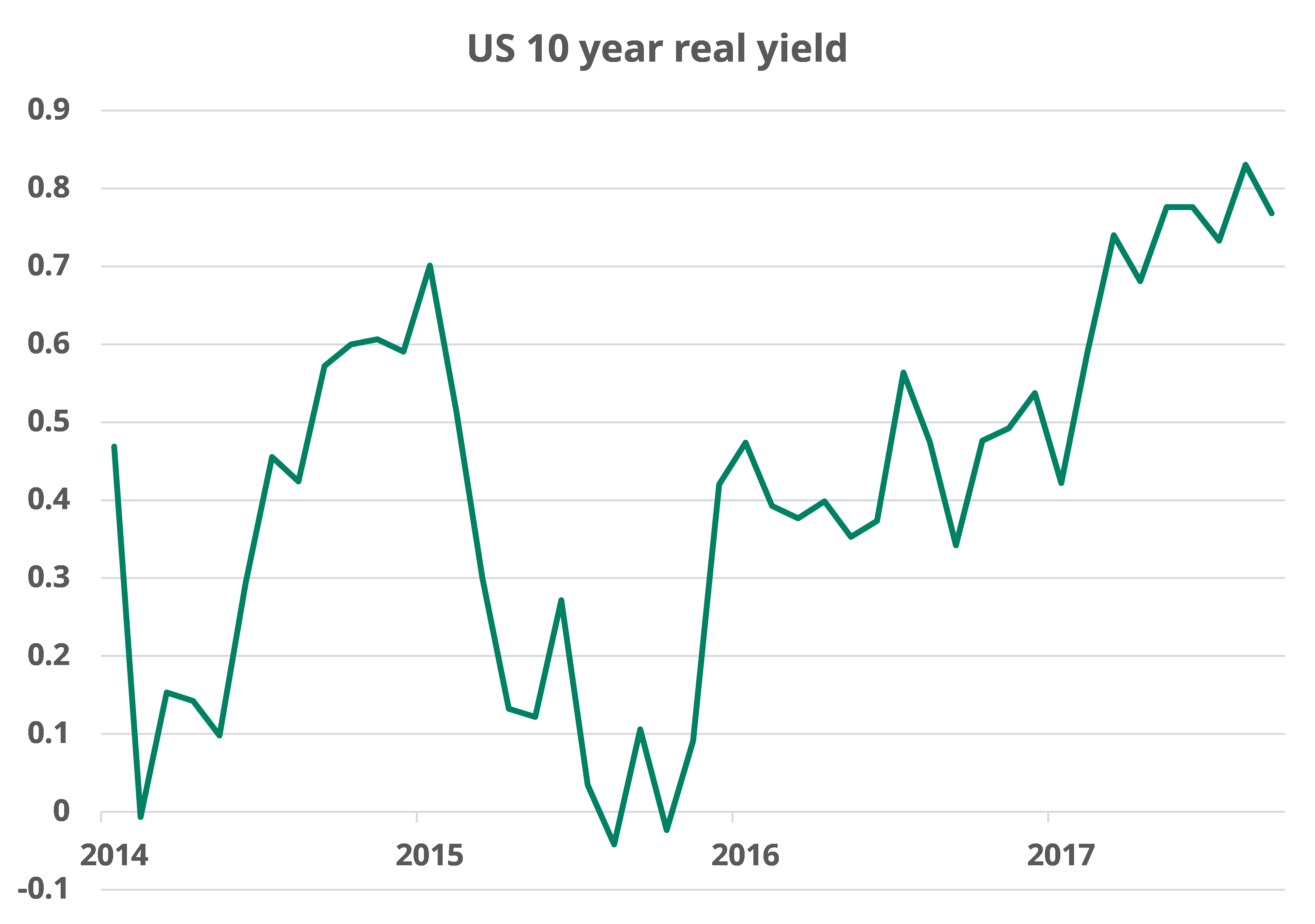

Unconventional monetary policies in various jurisdictions have been the main culprit for lower yields globally. Right now, markets are grappling with the fallout as these policies start to reverse. Financial conditions around the world have started to tighten after years of easy money and strong financial asset returns (Figure 3). Bond investors taking duration risk are at the forefront of this shift, and just as the interest rate sensitivity of their portfolios has hit its maximum point, they now face the inevitable headwinds of capital losses that will reduce the expected returns of their fixed income holdings for the foreseeable future.

Figure 3: US 10yr real yield

Source: Bloomberg, Daintree

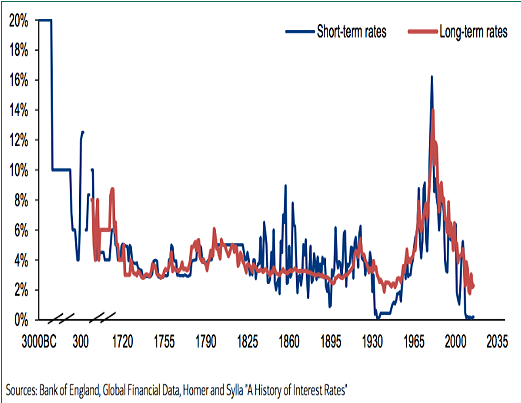

Capital losses are one issue such investors are facing; another related issue is defensiveness. Index-aware investment approaches are used by many investors in large part because they expect this part of their portfolio to offset losses in their equity portfolios. Historically, duration has been the most important driver of this defensive behaviour, causing fixed rate bonds to rise in value as interest rates and equity prices fall. But with bond yields at lows not seen for literally thousands of years (see Figure 4 below), bond prices do not have the same ability to rise as they once had. Of course, central banks in some jurisdictions have resorted to negative interest rates to increase the scope for bond prices to rise. Even then, however, there are greater limits to bond price appreciation now than have been the case for some time. As Figure 4 below shows, this has reduced the ability of a ‘traditional’, duration-heavy bond allocation to play the role of shock absorber in a multi-sector portfolio.

Figure 4: Interest rates are at extraordinarily low levels

Table: Equity versus bonds

Solutions

We have outlined a number of reasons why a benchmark-relative approach to fixed income is sub-optimal. Broadly, there are two courses of action investors might take as a result. The first is to change the nature of the benchmark.

Potential solution: Smart beta

A number of index providers have proposed changes to benchmark indices designed to address some of the issues listed above. Such approaches are commonly called ‘smart beta’ and involve altering the weighting methodology used to construct indices. In fixed income, one such change might be to weight bonds in an index according to metrics that impact issuers’ ability to repay debt. Sales, cash flow, or book value of assets are all metrics that come to mind; for example, a corporate bond benchmark may be constructed with larger weights to companies with better cash flow generation. Such a benchmark would go some way to alleviating the issue mentioned above, whereby traditional benchmarks shepherd investors toward companies that have a large amount of bonds on issue.

As such, a smart beta approach represents a more logical choice than a traditional benchmark for a fixed income investor. But such an approach does nothing to address any of the other issues we highlighted. This is why Daintree believes that the best way to manage a fixed income portfolio is to remove benchmarks from the discussion entirely.

Optimal solution: Absolute return: Benchmark agnostic

An investment in fixed income can be constructed in a very risk-aware way without the somewhat arbitrary restrictions that a benchmark introduces. For example, a benchmark may lead an investor to certain biases (intended or unintended) in terms of interest rate exposure, sectoral exposure and the like. If an investor does intend to bias a portfolio in a particular way, the manager can be directed to invest with the appropriate bias in mind – a benchmark index does not need to be in place to facilitate this. For example, duration exposure could be tightly controlled without the need for a traditional benchmark to play that role in portfolio construction.

The whole pitch to investors is therefore changed. Instead of outperforming a benchmark with minimal tracking error, success is defined as delivering the targeted return in the context of specifically targeted risk exposures that are tailored to bond investors, not to an index provider’s rules that may instead advantage bond issuers. The trade-off is that the manager has full access to global fixed income markets in order to construct portfolios that fulfill these goals.

This is what absolute return fixed income managers like Daintree Capital seek to achieve. Truly active management should mean that managers are not beholden to arbitrary benchmarks. End investors are able access a portfolio where expected returns and risk tolerances are carefully defined, and the following issues are ameliorated:

- Investments are made solely on the basis of attractive risk-adjusted expected returns. Careful research is undertaken across the global investment universe to find assets that are likely to achieve the best risk-adjusted returns, regardless of whether such assets are part of a given benchmark.

- Opportunity costs that result from restricting the investment opportunity set are avoided.

- Investments are made when risk-adjusted returns make sense to the investor, not when issuance suits the needs of the issuer.

- The focus is on achievement of a risk/return target that can be entirely customised to the needs of the end investor. The end investor does not instead have to adapt their requirements to a market benchmark.

- Interest rate risk can be reduced to appropriate levels given current market conditions. There is no incentive to ‘hug’ a market benchmark that may incorporate excessive exposure to interest rates.

- Returns are positive in absolute terms, not relative terms

Conclusion

At Daintree Capital, we ignore market benchmarks. Such benchmarks are flawed constructs that do not allow for adequate risk management, do not account for the market environment or for client needs and objectives, and indeed encourage perverse manager behavior. Instead, we assess our performance by aiming to consistently deliver our target return, while taking as little risk as possible. We never sit still: that means always looking for the most effective way to achieve our target return with minimal risk.

Disclaimer: Please note that these are the views of the writer and not necessarily the views of Daintree. This promotional statement does not take into account your investment objectives, particular needs or financial situation.